When People Make Devision Erros Over and Over Again in the Same Situation

Chapter x. Working Groups: Functioning and Decision Making

Group Conclusion Making

- Explain factors that tin can pb to procedure gain in group versus individual decision making.

- Explicate how groupthink can harm effective grouping decision making.

- Outline the ways that lack of information sharing tin can reduced decision-making quality in group contexts.

- Explain why brainstorming can ofttimes be counterproductive to audio decision making in groups.

- Draw how group polarization tin atomic number 82 groups to make more farthermost decisions than individuals.

- Explore important factors that pb juries to brand improve or worse decisions.

In the previous section, we explored some of the of import ways that being in a group affects individual group members' beliefs, and, in turn, influences the group'due south overall functioning. Likewise as achieving loftier levels of performance, another important task of groups is to make decisions. Indeed, we oft entrust groups, rather than individuals, with fundamental decisions in our societies—for example, those made by juries and political parties. An of import question to ask hither is whether we are right to trust groups more than individuals to reach audio decisions. Are many heads actually better than one?

It turns out that this question can be a difficult one to answer. For i thing, studying decision making is hard, because it is difficult to assess the quality of a conclusion on the basis of what was known at the time, independently of its consequence. This is peculiarly challenging as we naturally tend to look as well much at the outcome when we evaluate conclusion making, a miracle known as theconsequence bias. Moreover, studying determination making in laboratory environments has generally involved providing grouping members with more than information than they would typically take in the real world (Johnson & Johnson, 2012), and so the results may non ever generalize here.

Nevertheless, with these caveats in mind, it is possible to draw some tentative conclusions nearly when and why groups make better decisions than individuals, and as well when and why they may cease upwardly making worse ones.

Process Gains in Grouping versus Individual Decision Making

One of import factor that helps groups to outperform individuals on decision-making tasks is the blazon of interdependence they take. In general, positively interdependent (cooperative) groups tend to make better decisions than both negatively interdependent (competitive) groups and individuals, specially in complex tasks (Johnson & Johnson, 2012). These process gains come from a variety of factors. One is that when group members collaborate, they oft generate new ideas and solutions that they would non have arrived at individually (Watson, 1931). Group members are also more probable than individuals to discover and correct mistakes that tin can harm sound decision making (Ziller, 1957). They additionally have better collective retentiveness, meaning that many minds hold more relevant data than one, and superior transactive memory, which occurs when interactions between grouping members facilitate the recall of of import material (Forsyth, 2010). Also, when individual group members share information that is unique to them, they increase the full amount of data that the group tin can and then draw on when making sound decisions (Johnson & Johnson, 2012). Given these obvious advantages, are at that place e'er times when groups might brand less optimal decisions than individuals? If y'all have ever saturday in a group where, with hindsight, a fairly foolhardy determination was reached, then you lot probably already take your own answer to that question. The more than interesting question then becomes why are many heads sometimes worse than ane? Let's explore some of the about dramatic reasons.

Process Losses Due to Grouping Conformity Pressures: Groupthink

Groups can brand constructive decisions merely when they are able to brand use of the advantages outlined above that come with group membership. However, these weather condition are not e'er met in existent groups. Equally nosotros saw in the chapter opener, one case of a group process that tin atomic number 82 to very poor group decisions is groupthink.Groupthink occurs when a group that is made up of members who may actually be very competent and thus quite capable of making excellent decisions even so ends up making a poor one as a result of a flawed group procedure and potent conformity pressures (Businesswoman, 2005; Janis, 2007).

Groupthink is more probable to occur in groups in which the members are feeling potent social identity—for instance, when there is a powerful and directive leader who creates a positive group feeling, and in times of stress and crisis when the group needs to rise to the occasion and brand an important conclusion. The problem is that groups suffering from groupthink become unwilling to seek out or talk over discrepant or unsettling information about the topic at hand, and the group members practise not express contradictory opinions. Because the group members are afraid to limited ideas that contradict those of the leader or to bring in outsiders who accept other information, the grouping is prevented from making a fully informed conclusion. Figure 10.9, "Antecedents and Outcomes of Groupthink," summarizes the bones causes and outcomes of groupthink.

Although at to the lowest degree some scholars are skeptical of the importance of groupthink in real group decisions (Kramer, 1998), many others accept suggested that groupthink was involved in a number of well-known and important, but very poor, decisions fabricated by government and business groups. Fundamental historical decisions analyzed in terms of groupthink include the conclusion to invade Republic of iraq made by President George Bush-league and his advisors, with the support of other national governments, including those from the Uk, Spain, Italia, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, and Commonwealth of australia; the determination of President John F. Kennedy and his advisors to commit U.Southward. forces to assist with an invasion of Cuba, with the goal of overthrowing Fidel Castro in 1962; and the policy of appeasement of Nazi Germany pursued by many European leaders in 1930s, in the pb-up to World War II. Groupthink has besides been applied to some less well-known, just as well important, domains of conclusion making, including pack journalism (Matusitz, & Breen, 2012). Intriguingly, groupthink has even been used to effort to business relationship for perceived anti-right-wing political biases of social psychologists (Redding, 2012).

Careful analyses of the decision-making process in the historical cases outlined above have documented the office of conformity pressures. In fact, the group process often seems to be arranged to maximize the corporeality of conformity rather than to foster costless and open discussion. In the meetings of the Bay of Pigs informational committee, for instance, President Kennedy sometimes demanded that the group members give a voice vote regarding their private opinions before the grouping actually discussed the pros and cons of a new thought. The consequence of these conformity pressures is a general unwillingness to limited ideas that do not lucifer the group norm.

The pressures for conformity also lead to the state of affairs in which merely a few of the grouping members are actually involved in conversation, whereas the others do not limited whatever opinions. Considering little or no dissent is expressed in the group, the group members come to believe that they are in complete agreement. In some cases, the leader may even select individuals (known asmindguards) whose job it is to help quash dissent and to increment conformity to the leader's opinions.

An consequence of the high levels of conformity institute in these groups is that the group begins to see itself as extremely valuable and of import, highly capable of making high-quality decisions, and invulnerable. In short, the group members develop extremely loftier levels of conformity and social identity. Although this social identity may accept some positive outcomes in terms of a commitment to work toward group goals (and information technology certainly makes the group members feel good virtually themselves), it also tends to result in illusions of invulnerability, leading the group members to feel that they are superior and that they practice not demand to seek exterior data. Such a situation is often conducive to poor decision making, which can result in tragic consequences.

Interestingly, the composition of the group itself tin can affect the likelihood of groupthink occurring. More diverse groups, for instance, can assistance to ensure that a wider range of views are bachelor to the grouping in making their decision, which can reduce the risk of groupthink. Thinking back to our case report, the more homogeneous the grouping are in terms of internal characteristics such as behavior, and external characteristics such as gender, the more at risk of groupthink they may get (Kroon, Van Kreveld, & Rabbie, 1992). Perhaps, then, mixed gender corporate boards are more successful partly because they are meliorate able to avoid the dangerous miracle of groupthink.

Cognitive Procedure Losses: Lack of Data Sharing

Although group give-and-take mostly improves the quality of a group'south decisions, this will only exist true if the group discusses the information that is near useful to the decision that needs to exist made. One difficulty is that groups tend to hash out some types of data more than others. In addition to the pressures to focus on information that comes from leaders and that is consistent with group norms, give-and-take is influenced by the way the relevant information is originally shared among the grouping members. The problem is that grouping members tend to discuss information that they all accept access to while ignoring every bit important information that is bachelor to just a few of the members, a tendency known as theshared information bias (Faulmüller, Kerschreiter, Mojzisch, & Schulz-Hardt, 2010; Reimer, Reimer, & Czienskowski (2010).

Research Focus

Poor Information Sharing in Groups

In one sit-in of the shared information bias, Stasser and Titus (1985) used an experimental blueprint based on the hidden profile task, equally shown in Table ten.1. Students read descriptions of 2 candidates for a hypothetical student trunk presidential election and and then met in groups to discuss and choice the best candidate. The information well-nigh the candidates was arranged so that one of the candidates (Candidate A) had more positive qualities overall in comparison with the other (Candidate B). Reflecting this superiority, in groups in which all the members were given all the information about both candidates, the members chose Candidate A 83% of the fourth dimension after their discussion.

Table 10.1 Hidden Profiles

| Group member | Information favoring Candidate A | Information favoring Candidate B |

|---|---|---|

| Ten | a1, a2 | b1, b2, b3 |

| Y | a1, a3 | b1, b2, b3 |

| Z | a1, a4 | b1, b2, b3 |

| This is an case of the type of "hidden profile" that was used by Stasser and Titus (1985) to study information sharing in grouping give-and-take. Stasser, Thousand., & Titus, W. (1985). Pooling of unshared information in group decision making: Biased data sampling during discussion.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 1467–1478. (The researchers' profiles were really somewhat more than complicated.) The three pieces of favorable information about Candidate B (b1, b2, and b3) were seen past all of the group members, simply the favorable data about Candidate A (a1, a2, a3, and a4) was not given to everyone. Considering the group members did not share the information about Candidate A, Candidate B was erroneously seen as a better choice. | ||

Withal, in some cases, the experimenters made the task more than hard past creating a "subconscious profile," in which each member of the group received but part of the data. In these cases, although all the information was potentially bachelor to the group, it was necessary that it be properly shared to make the right choice. Specifically, in this example, in which the information favoring Candidate B was shared, but the information favoring Candidate A was not, simply 18% of the groups chose A, whereas the others chose the inferior candidate. This occurred because although the grouping members had access to all the positive information collectively, the information that was not originally shared among all the group members was never discussed. Furthermore, this bias occurred even in participants who were given explicit instructions to be sure to avoid expressing their initial preferences and to review all the available facts (Stasser, Taylor, & Hanna, 1989).

Although the tendency to share information poorly seems to occur quite frequently, at least in experimentally created groups, it does not occur as nether all conditions. For one, groups have been found to better share information when the group members believe that at that place is a correct answer that tin exist found if there is sufficient discussion (Stasser & Stewart, 1992), and if they are forced to go on their discussion fifty-fifty after they believe that they have discussed all the relevant information (Larson, Foster-Fishman, & Keys, 1994). These findings suggest that an important chore of the group leader is to proceed grouping give-and-take until he or she is convinced that all the relevant information has been addressed.

The construction of the group volition too influence information sharing (Stasser & Taylor, 1991). Groups in which the members are more physically separated and thus have difficulty communicating with each other may find that they need to reorganize themselves to amend advice. And the condition of the grouping members tin also exist of import. Group members with lower status may have less confidence and thus exist unlikely to express their opinions. Wittenbaum (1998) found that group members with higher status were more likely to share new information. Nonetheless, those with college status may sometimes boss the discussion, fifty-fifty if the information that they have is not more valid or of import (Hinsz, 1990). Groups are also likely to share unique information when the group members practice not initially know the alternatives that need to be determined or the preferences of the other grouping members (Mojzisch & Schulz-Hardt, 2010; Reimer, Reimer, & Hinsz, 2010).

Findings showing that groups neither share nor discuss originally unshared information take very disconcerting implications for group decision making considering they propose that group give-and-take is likely to lead to very poor judgments. Not but is unshared information not brought to the table, but because the shared data is discussed repeatedly, it is likely to be seen as more than valid and to have a greater influence on decisions every bit a outcome of its high cognitive accessibility. It is non uncommon that individuals within a working grouping come up to the discussion with different types of information, and this unshared data needs to exist presented. For instance, in a meeting of a blueprint team for a new building, the architects, the engineers, and the client representatives will accept unlike and potentially incompatible information. Thus leaders of working groups must be aware of this problem and piece of work hard to foster open climates that encourages information sharing and give-and-take.

Given its obvious pitfalls, an interesting question to ask is why the shared data bias seems to be and so pervasive. Recalling the confirmation bias that we discussed in the chapter on social cognition, peradventure information technology reflects this tendency played out at the grouping level, where grouping members collaborate to provide confirmatory evidence for each other's positions. Leading on from this, it could also reverberate the trend for people to wish to utilise groups to reinforce their ain views. Perhaps sometimes groups go places where people seek to mutually validate each other'southward shared perspectives, to the detriment of them searching out the alternatives. If these ideas are correct, given that we often choose to associate with similar others, so it may exist of import to seek out the views of grouping members that are likely to be most different from our own, in seeking to weaken the damaging furnishings of the shared data bias (Morrow & Deidan, 1992).

Cerebral Process Losses: Ineffective Brainstorming

1 technique that is frequently used to produce creative decisions in working groups is known as brainstorming. The technique was first developed by Osborn (1953) in an effort to increase the effectiveness of group sessions at his advertising bureau. Osborn had the idea that people might be able to effectively utilise their brains to "storm" a problem by sharing ideas with each other in groups. Osborn felt that creative solutions would be increased when the group members generated a lot of ideas and when judgments about the quality of those ideas were initially deferred and merely later evaluated. Thus brainstorming was based on the following rules:

- Each group member was to create as many ideas every bit possible, no matter how silly, unimportant, or unworkable they were thought to be.

- As many ideas as possible were to be generated by the group.

- No one was allowed to offer opinions nearly the quality of an thought (even ane'due south own).

- The group members were encouraged and expected to alter and expand upon other'due south ideas.

Researchers have devoted considerable effort to testing the effectiveness of brainstorming, and yet, despite the creativeness of the idea itself, there is very footling evidence to suggest that it works (Diehl & Stroebe, 1987, 1991; Stroebe & Diehl, 1994). In fact, virtually all individual studies, as well equally meta-analyses of those studies, discover that regardless of the verbal instructions given to a grouping, brainstorming groups do not generate as many ideas as one would await, and the ideas that they exercise generate are usually of lesser quality than those generated by an equal number of individuals working alone who and so share their results. Thus brainstorming represents still another instance of a instance in which, despite the expectation of a process gain by the group, a procedure loss is instead observed.

A number of explanations have been proposed for the failure of brainstorming to exist effective, and many of these take been establish to exist important. 1 obvious problem is social loafing by the group members, and at least some research suggests that this does cause office of the problem. For instance, Paulus and Dzindolet (1993) found that social loafing in brainstorming groups occurred in role because individuals perceived that the other group members were not working very hard, and they matched they own beliefs to this perceived norm. To test the function of social loafing more directly, Diehl and Stroebe (1987) compared contiguous brainstorming groups with equal numbers of individuals who worked alone; they found that confront-to-face brainstorming groups generated fewer and less creative solutions than did an equal number of equivalent individuals working past themselves. However, for some of the face-to-face up groups, the researchers gear up up a television photographic camera to record the contributions of each of the participants in order to brand individual contributions to the word identifiable. Being identifiable reduced social loafing and increased the productivity of the individuals in the face-to-face groups; but the face up-to-face up groups still did not perform as well as the individuals.

Even though individuals in brainstorming groups are told that no evaluation of the quality of the ideas is to be made, and thus that all ideas are adept ones, individuals might nevertheless be unwilling to country some of their ideas in brainstorming groups considering they are afraid that they will be negatively evaluated past the other group members. When individuals are told that other group members are more knowledgeable than they are, they reduce their ain contributions (Collaros & Anderson, 1969), and when they are convinced that they themselves are experts, their contributions increment (Diehl & Stroebe, 1987).

Although social loafing and evaluation apprehension seem to cause some of the problem, the most important difficulty that reduces the effectiveness of brainstorming in face-to-face groups is that being with others in a group hinders opportunities for idea product and expression. In a group, but one person can speak at a time, and this can cause people to forget their ideas because they are listening to others, or to miss what others are saying because they are thinking of their own ideas, a problem known equallyproduct blocking. Considered another manner, production blocking occurs because although individuals working alone can spend the unabridged bachelor fourth dimension generating ideas, participants in face-to-face groups must perform other tasks too, and this reduces their inventiveness.

Diehl and Stroebe (1987) demonstrated the importance of production blocking in another experiment that compared individuals with groups. In this experiment, rather than changing things in the real group, they created production blocking in the individual conditions through a plow-taking procedure, such that the individuals, who were working in private cubicles, had to express their ideas verbally into a microphone, but they were only able to speak when none of the other individuals was speaking. Having to coordinate in this way decreased the performance of individuals such that they were no longer ameliorate than the face up-to-face groups.

Follow-upwards research (Diehl & Stroebe, 1991) showed that the main factor responsible for productivity loss in contiguous brainstorming groups is that the grouping members are not able to make practiced apply of the time they are forced to spend waiting for others. While they are waiting, they tend to forget their ideas because they must concentrate on negotiating when it is going to be their plough to speak. In fact, even when the researchers gave the face-to-face groups extra time to perform the chore (to make up for having to expect for others), they nonetheless did not achieve the level of productivity of the individuals. Thus the necessity of monitoring the behavior of others and the filibuster that is involved in waiting to be able to express one's ideas reduce the ability to think creatively (Gallupe, Cooper, Grise, & Bastianutti, 1994).

Although brainstorming is a classic example of a group process loss, there are ways to make information technology more effective. One variation on the brainstorming idea is known every bit thenominal group technique (Delbecq, Van de Ven, & Gustafson, 1975). The nominal group technique capitalizes on the use of individual sessions to generate initial ideas, followed by face-to-face group meetings to discuss and build on them. In this approach, participants first work alone to generate and write down their ideas before the group discussion starts, and the group and so records the ideas that are generated. In addition, a round-robin procedure is used to make sure that each individual has a hazard to communicate his or her ideas. Other similar approaches include the Delphi technique (Clayton, 1997; Hornsby, Smith, & Gupta, 1994) and Synectics (Stein, 1978).

Contemporary advances in technology have created the ability for individuals to work together on inventiveness tasks via computer. These computer systems, generally known every bitgroup support systems, are used in many businesses and other organizations. One utilise involves brainstorming on creativity tasks. Each private in the group works at his or her own computer on the problem. As he or she writes suggestions or ideas, they are passed to the other grouping members via the computer network, so that each individual tin can see the suggestions of all the grouping members, including their own.

A number of research programs have found that electronic brainstorming is more effective than face-to-face brainstorming (Dennis & Valacich, 1993; Gallupe, Cooper, Grise, & Bastianutti, 1994; Siau, 1995), in big part because information technology reduces the product blocking that occurs in face-to-face up groups. Groups that work together near rather than face-to-face take also been found to be more likely to share unique data (Mesmer-Magnus, DeChurch, Jimenez-Rodriguez, Wildman, & Schuffler, 2011). Each individual has the comments of all the other group members handy and tin can read them when it is convenient. The individual can alternating between reading the comments of others and writing his or her ain comments and therefore is non required to expect to express his or her ideas. In addition, electronic brainstorming can exist effective because it reduces evaluation apprehension, particularly when the participants' contributions are anonymous (Connolly, Routhieaux, & Schneider, 1993; Valacich, Jessup, Dennis, & Nunamaker, 1992).

In summary, the nigh important conclusion to be drawn from the literature on brainstorming is that the technique is less effective than expected because group members are required to do other things in addition to existence creative. However, this does not necessarily mean that brainstorming is not useful overall, and modifications of the original brainstorming procedures accept been found to be quite effective in producing creative thinking in groups. Techniques that make use of initial private thought, which is afterward followed by group discussion, represent the best approaches to brainstorming and group creativity. When you are in a group that needs to make a decision, yous can make utilize of this knowledge. Ask the grouping members to spend some time thinking almost and writing down their own ideas before the group begins its word.

Group Polarization

One common decision-making task of groups is to come up to a consensus regarding a judgment, such as where to hold a party, whether a defendant is innocent or guilty, or how much coin a corporation should invest in a new product. Whenever a bulk of members in the grouping favors a given stance, even if that majority is very slim, the group is likely to cease up adopting that majority stance. Of form, such a result would exist expected, since, as a result of conformity pressures, the group'south terminal judgment should reverberate the average of group members' initial opinions.

Although groups generally exercise show pressures toward conformity, the tendency to side with the majority after group discussion turns out to be even stronger than this. It is unremarkably found that groups make even more extreme decisions, in the management of the existing norm, than we would predict they would, given the initial opinions of the group members. Group polarization is said to occur when,after discussion, the attitudes held by the individual group members become more farthermost than they were earlier the grouping began discussing the topic (Brauer, Judd, & Gliner, 2006; Myers, 1982). This may seem surprising, given the widespread belief that groups tend to push people toward consensus and the middle-footing in decision making. Actually, they may ofttimes lead to more than extreme decisions beingness made than those that individuals would take taken on their ain.

Group polarization was initially observed using problems in which the group members had to indicate how an individual should choose between a risky, but very positive, upshot and a certain, only less desirable, upshot (Stoner, 1968). Consider the following question:

Frederica has a secure job with a large bank. Her salary is adequate just unlikely to increment. Still, Frederica has been offered a task with a relatively unknown startup visitor in which the likelihood of failure is high and in which the salary is dependent upon the success of the company. What is the minimum probability of the startup company'due south success that you would find acceptable to arrive worthwhile for Frederica to accept the task? (cull 1)

1 in x, three in x, 5 in x, seven in 10, 9 in 10

Research has constitute group polarization on these types of decisions, such that the group recommendation is more than risky (in this case, requiring a lower probability of success of the new company) than the average of the individual group members' initial opinions. In these cases, the polarization can be explained partly in terms of improvidence of responsibility (Kogan & Wallach, 1967). Considering the group as a whole is taking responsibility for the decision, the individual may exist willing to take a more than extreme stand, since he or she tin share the blame with other grouping members if the risky decision does non piece of work out.

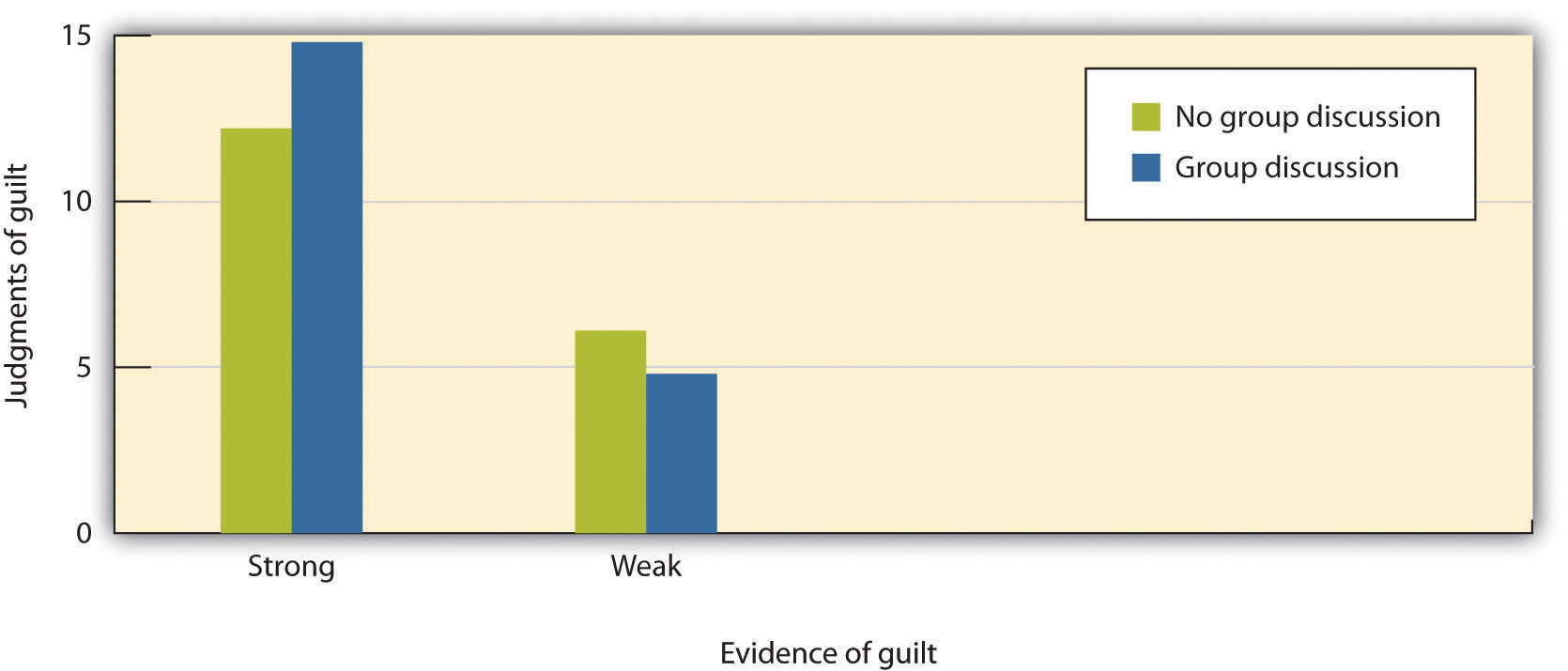

Simply grouping polarization is not limited to decisions that involve run a risk. For example, in an experiment past Myers and Kaplan (1976), groups of students were asked to assess the guilt or innocence of defendants in traffic cases. The researchers also manipulated the forcefulness of the evidence confronting the defendant, such that in some groups the testify was strong and in other groups the prove was weak. This resulted in two groups of juries—some in which the majority of the students initially favored conviction (on the footing of the strong evidence) and others in which a bulk initially favored acquittal (on the footing of only weak evidence). The researchers asked the individuals to limited their opinions about the guilt of the defendant both earlier and subsequently the jury deliberated.

As yous can see in Figure 10.10, "Group Polarization," the opinions that the individuals held about the guilt or innocence of the defendants were found to be more extreme after discussion than they were, on average, before the give-and-take began. That is, members of juries in which the majority of the individuals initially favored conviction became more probable to believe the defendant was guilty later the discussion, and members of juries in which the majority of the individuals initially favored acquittal became more than probable to believe the defendant was innocent after the discussion. Similarly, Myers and Bishop (1970) constitute that groups of higher students who had initially racist attitudes became more racist after group give-and-take, whereas groups of college students who had initially antiracist attitudes became less racist after group discussion. Like findings accept been found for groups discussing a very wide variety of topics and across many unlike cultures.

The juries in this inquiry were given either potent or weak evidence virtually the guilt of a accused and so were either allowed or not allowed to hash out the evidence before making a final determination. Demonstrating group polarization, the juries that discussed the example made significantly more farthermost decisions than did the juries that did not discuss the instance. Data are from Myers and Kaplan (1976).

Grouping polarization does not occur in all groups and in all settings but tends to happen well-nigh often when two conditions are present: Beginning, the group members must accept an initial leaning toward a given stance or determination. If the group members generally support liberal policies, their opinions are likely to go even more liberal later discussion. But if the grouping is made upwardly every bit of both liberals and conservatives, group polarization would not be expected. Second, grouping polarization is strengthened by discussion of the topic. For example, in the enquiry by Myers and Kaplan (1976) simply reported, in some experimental atmospheric condition, the group members expressed their opinions but did non discuss the issue, and these groups showed less polarization than groups that discussed the issue.

Group polarization has also been observed in important real-world contexts, including financial decision making in corporate boardrooms (Cheng & Chiou, 2008; Zhu, 2010). It has also been argued that the contempo polarization in political attitudes in many countries, for case in the United States betwixt the "blue" Democratic states versus the "red" Republican states, is occurring in large part because each group spends fourth dimension communicating with other similar-minded group members, leading to more extreme opinions on each side. And some have argued that terrorist groups develop their farthermost positions and engage in violent behaviors as a result of the group polarization that occurs in their everyday interactions (Drummond, 2002; McCauley, 1989). As the group members, all of whom initially take some radical beliefs, see and hash out their concerns and desires, their opinions polarize, assuasive them to go progressively more extreme. Because they are also abroad from any other influences that might moderate their opinions, they may somewhen become mass killers.

Group polarization is the upshot of both cognitive and affective factors. The general idea of the persuasive arguments arroyo to explaining grouping polarization is cognitive in orientation. This approach assumes that there is a set of potential arguments that back up any given opinion and some other set of potential arguments that refute that stance. Furthermore, an individual's current opinion nearly the topic is predicted to be based on the arguments that he or she is currently aware of. During grouping word, each member presents arguments supporting his or her private opinions. And because the grouping members are initially leaning in one direction, it is expected that there will be many arguments generated that support the initial leaning of the grouping members. As a result, each member is exposed to new arguments supporting the initial leaning of the group, and this predominance of arguments leaning in one management polarizes the opinions of the group members (Van Swol, 2009). Supporting the predictions of persuasive arguments theory, inquiry has shown that the number of novel arguments mentioned in word is related to the amount of polarization (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978) and that there is likely to be little grouping polarization without discussion (Clark, Crockett, & Archer, 1971). Notice here the parallels betwixt the persuasive arguments approach to group polarization and the concept of informational conformity.

Simply grouping polarization is in part based on the melancholia responses of the individuals—and especially the social identity they receive from being good group members (Hogg, Turner, & Davidson, 1990; Mackie, 1986; Mackie & Cooper, 1984). The thought hither is that group members, in their desire to create positive social identity, attempt to differentiate their group from other implied or actual groups by adopting extreme beliefs. Thus the corporeality of grouping polarization observed is expected to be determined not but by the norms of the ingroup but besides by a movement abroad from the norms of other relevant outgroups. In short, this explanation says that groups that have well-defined (extreme) beliefs are meliorate able to produce social identity for their members than are groups that have more moderate (and potentially less clear) behavior. Once over again, notice the similarity of this account of polarization to the notion of normative conformity.

Group polarization effects are stronger when the group members have high social identity (Abrams, Wetherell, Cochrane, & Hogg, 1990; Hogg, Turner, & Davidson, 1990; Mackie, 1986). Diane Mackie (1986) had participants listen to three people discussing a topic, supposedly then that they could become familiar with the issue themselves to aid them make their ain decisions. Even so, the individuals that they listened to were said to be members of a group that they would be joining during the upcoming experimental session, members of a group that they were not expecting to join, or some individuals who were not a grouping at all. Mackie plant that the perceived norms of the (future) ingroup were seen as more extreme than those of the other group or the individuals, and that the participants were more than likely to hold with the arguments of the ingroup. This finding supports the idea that grouping norms are perceived as more extreme for groups that people place with (in this instance, because they were expecting to join it in the futurity). And another experiment by Mackie (1986) too supported the social identity prediction that the existence of a rival outgroup increases polarization every bit the grouping members attempt to differentiate themselves from the other group by adopting more extreme positions.

Taken together and so, the enquiry reveals that another potential problem with group decision making is that it can be polarized. These changes toward more extreme positions accept a diverseness of causes and occur more under some conditions than others, but they must be kept in mind whenever groups come together to make important decisions.

Social Psychology in the Public Interest

Decision Making by a Jury

Although many countries rely on the decisions of judges in civil and criminal trials, the jury is the foundation of the legal system in many other nations. The notion of a trial past one's peers is based on the assumption that boilerplate individuals tin brand informed and off-white decisions when they work together in groups. But given all the bug facing groups, social psychologists and others oft wonder whether juries are really the best way to make these important decisions and whether the particular composition of a jury influences the likely outcome of its deliberation (Lieberman, 2011).

As pocket-sized working groups, juries have the potential to produce either good or poor decisions, depending on many of the factors that nosotros take discussed in this affiliate (Bornstein & Greene, 2011; Hastie, 1993; Winter & Robicheaux, 2011). And again, the ability of the jury to make a skilful decision is based on both person characteristics and grouping process. In terms of person variables, there is at least some bear witness that the jury member characteristics do thing. For ane, individuals who have already served on juries are more likely to exist seen as experts, are more than likely to exist called as jury foreperson, and requite more than input during the deliberation (Stasser, Kerr, & Bray, 1982). It has besides been found that status matters—jury members with higher-condition occupations and education, males rather than females, and those who talk get-go are more likely be chosen as the foreperson, and these individuals besides contribute more to the jury word (Stasser et al., 1982). And every bit in other pocket-sized groups, a minority of the group members mostly dominate the jury word (Hastie, Penrod, & Pennington, 1983), And there is frequently a trend toward social loafing in the grouping (Najdowski, 2010). As a issue, relevant information or opinions are likely to remain unshared considering some individuals never or rarely participate in the give-and-take.

Perhaps the strongest evidence for the importance of fellow member characteristics in the decision-making process concerns the choice of death-qualified juries in trials in which a potential sentence includes the capital punishment. In order to exist selected for such a jury, the potential members must point that they would, in principle, be willing to recommend the death punishment equally a punishment. In some countries, potential jurors who signal being opposed to the death sentence cannot serve on these juries. Still, this selection process creates a potential bias because the individuals who say that they would not under whatever condition vote for the death penalty are likewise more likely to be rigid and punitive and thus more likely to observe defendants guilty, a situation that increases the chances of a conviction for defendants (Ellsworth, 1993).

Although in that location are at least some fellow member characteristics that have an influence upon jury determination making, group procedure, as in other working groups, plays a more important role in the outcome of jury decisions than do fellow member characteristics. Similar any group, juries develop their own private norms, and these norms can have a profound bear upon on how they reach their decisions. Analysis of group procedure within juries shows that different juries accept very dissimilar approaches to reaching a verdict. Some spend a lot of fourth dimension in initial planning, whereas others immediately spring correct into the deliberation. And some juries base their discussion around a review and reorganization of the prove, waiting to have a vote until it has all been considered, whereas other juries start determine which decision is preferred in the group by taking a poll and and so (if the get-go vote does not pb to a last verdict) organize their give-and-take around these opinions. These ii approaches are used virtually every bit oftentimes simply may in some cases atomic number 82 to different decisions (Hastie, 2008).

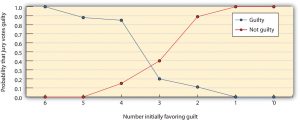

Maybe most of import, conformity pressures accept a strong impact on jury decision making. As yous can see in Figure 10.11, when at that place are a greater number of jury members who concur the majority position, it becomes more than and more sure that their stance volition prevail during the discussion. This is non to say that minorities cannot ever exist persuasive, but information technology is very difficult for them. The strong influence of the bulk is probably due to both informational conformity (i.e., that in that location are more arguments supporting the favored position) and normative conformity (people are less probable to want to be seen as disagreeing with the majority opinion).

This figure shows the decisions of half dozen-member mock juries that fabricated "majority rules" decisions. When the majority of the six initially favored voting guilty, the jury almost always voted guilty, and when the bulk of the six initially favored voting innocent, the jury nearly always voted innocence. The juries were often hung (could not brand a decision) when the initial split was three to three. Data are from Stasser, Kerr, and Bray (1982).

Enquiry has besides plant that juries that are evenly split (three to three or half dozen to six) tend to show a leniency bias by voting toward acquittal more oftentimes than they vote toward guilt, all other factors being equal (MacCoun & Kerr, 1988). This is in part because juries are usually instructed to assume innocence unless there is sufficient evidence to ostend guilt—they must apply a brunt of proof of guilt "beyond a reasonable uncertainty." The leniency bias in juries does not always occur, although it is more likely to occur when the potential penalty is more severe (Devine et al., 2004; Kerr, 1978).

Given what you now know most the potential difficulties that groups face in making proficient decisions, you might be worried that the verdicts rendered by juries may non be especially effective, authentic, or off-white. Even so, despite these concerns, the testify suggests that juries may not do as badly as nosotros would expect. The deliberation process seems to cancel out many individual juror biases, and the importance of the conclusion leads the jury members to carefully consider the evidence itself.

- Under certain situations, groups tin can prove significant procedure gains in regards to decision making, compared with individuals. Nevertheless, there are a number of social forces that can hinder effective group decision making, which can sometimes lead groups to testify process losses.

- Some group procedure losses are the result of groupthink—when a group, as event of a flawed group procedure and stiff conformity pressures, makes a poor judgment.

- Process losses may result from the tendency for groups to hash out data that all members have access to while ignoring every bit important data that is bachelor to merely a few of the members.

- Brainstorming is a technique designed to foster inventiveness in a grouping. Although brainstorming often leads to group process losses, alternative approaches, including the employ of group back up systems, may be more constructive.

- Group decisions can also be influenced past group polarization—when the attitudes held by the individual group members go more extreme than they were earlier the grouping began discussing the topic.

- Agreement grouping processes tin assist us improve understand the factors that lead juries to make ameliorate or worse decisions.

- Consider a time when a group that you belonged to experienced a process gain, and another fourth dimension showed a process loss in terms of determination making. Which of the factors discussed in this department practise you remember help to explain these two different outcomes?

- Describe a current social or political issue where you have seen groupthink in activity. What features of groupthink outlined in this section were particularly evident? When in your own life accept yous been in a group situation where groupthink was evident? What conclusion was reached and what was the outcome for yous?

- When take y'all been in a group that has non shared information effectively? Why do you call up that this happened and what were the consequences?

- Outline 2 situations, one when you lot were in a group that used brainstorming and you experience that it was helpful to the group decision-making process, and some other when y'all recall information technology was a hindrance. Why practice you call back the brainstorming had these opposite furnishings on the groups in the two situations?

- What examples of group polarization have you seen in the media recently? How well do the ideas of normative and informational conformity explicate why polarization occurred in these situations? What other factors might also have been at piece of work?

- If y'all or someone y'all knew had a choice to be tried by either a approximate or a jury, taking into business relationship the research in this department, which would you choose, and why?

References

Abrams, D., Wetherell, Grand., Cochrane, S., & Hogg, M. (1990). Knowing what to think past knowing who you are: Cocky-categorization and the nature of norm germination, conformity, and group polarization. British Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 97–119.

Baron, R. S. (2005). Then correct information technology's incorrect: Groupthink and the ubiquitous nature of polarized group conclusion making. In K. P. Zanna (Ed.),Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 37, pp. 219–253). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Bookish Press.

Bornstein, B. H., & Greene, E. (2011). Jury decision making: Implications for and from psychology.Electric current Directions in Psychological Science, xx(ane), 63–67.

Brauer, Chiliad., Judd, C. Chiliad., & Gliner, Yard. D. (2006). The furnishings of repeated expressions on attitude polarization during group discussions. In J. One thousand. Levine & R. L. Moreland (Eds.),Small groups (pp. 265–287). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Cheng, P.-Y., & Chiou, W.-B. (2008). Framing effects in group investment conclusion making: Role of group polarization.Psychological Reports, 102(1), 283–292.

Clark, R. D., Crockett, W. H., & Archer, R. 50. (1971). Risk-every bit-value hypothesis: The human relationship between perception of cocky, others, and the risky shift.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 20, 425–429.

Clayton, M. J. (1997). Delphi: A technique to harness proficient stance for critical conclusion-making tasks in instruction.Educational Psychology, 17(four), 373–386. doi: 10.1080/0144341970170401.

Collaros, P. A., & Anderson, I. R. (1969). Result of perceived expertness upon inventiveness of members of brainstorming groups.Periodical of Applied Psychology, 53, 159–163.

Connolly, T., Routhieaux, R. L., & Schneider, Southward. Thou. (1993). On the effectiveness of group brainstorming: Examination of one underlying cognitive mechanism.Small Group Research, 24(four), 490–503.

Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., & Gustafson, D. H. (1975).Grouping techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and delphi processes. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Dennis, A. R., & Valacich, J. Southward. (1993). Computer brainstorms: More heads are better than one.Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 531–537.

Devine, D. J., Olafson, Thousand. Grand., Jarvis, L. L., Bott, J. P., Clayton, L. D., & Wolfe, J. G. T. (2004). Explaining jury verdicts: Is leniency bias for real?Journal of Practical Social Psychology, 34(x), 2069–2098.

Diehl, 1000., & Stroebe, Due west. (1987). Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(3), 497–509.

Diehl, Yard., & Stroebe, W. (1991). Productivity loss in idea-generating groups: Tracking down the blocking effect.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 392–403.

Drummond, J. T. (2002). From the Northwest Imperative to global jihad: Social psychological aspects of the structure of the enemy, political violence, and terror. In C. East. Stout (Ed.),The psychology of terrorism: A public understanding (Vol. ane, pp. 49–95). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group.

Ellsworth, P. C. (1993). Some steps between attitudes and verdicts. In R. Hastie (Ed.),Inside the juror: The psychology of juror decision making. New York, NY: Cambridge University Printing.

Faulmüller, N., Kerschreiter, R., Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, Southward. (2010). Across group-level explanations for the failure of groups to solve hidden profiles: The private preference effect revisited.Grouping Processes and Intergroup Relations, 13(5), 653–671.

Forsyth, D. (2010). Group dynamics (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Gallupe, R. B., Cooper, W. H., Grise, K.-L., & Bastianutti, L. M. (1994). Blocking electronic brainstorms.Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(ane), 77–86.

Hastie, R. (1993).Inside the juror: The psychology of juror determination making. New York, NY: Cambridge University Printing.

Hastie, R. (2008). What's the story? Explanations and narratives in civil jury decisions. In B. H. Bornstein, R. L. Wiener, R. Schopp, & S. Fifty. Willborn (Eds.),Ceremonious juries and civil justice: Psychological and legal perspectives (pp. 23–34). New York, NY: Springer Scientific discipline + Business Media.

Hastie, R., Penrod, South. D., & Pennington, N. (1983).Inside the jury. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hinsz, V. B. (1990). Cognitive and consensus processes in grouping recognition memory performance.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 705–718.

Hogg, K. A., Turner, J. C., & Davidson, B. (1990). Polarized norms and social frames of reference: A test of the self-categorization theory of group polarization.Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 11(1), 77–100.

Hornsby, J. S., Smith, B. N., & Gupta, J. Due north. D. (1994). The impact of decision-making methodology on job evaluation outcomes: A await at 3 consensus approaches.Group and Organization Management, 19(one), 112–128.

Janis, I. L. (2007). Groupthink. In R. P. Vecchio (Ed.),Leadership: Understanding the dynamics of power and influence in organizations (2nd ed., pp. 157–169). Notre Dame, IN: Academy of Notre Dame Press.

Johnson, D.West., & Johnson, F.P. (2012).Joining together – group theory and group skills (11th ed). Boston: Allyn and Salary.

Kerr, Northward. L. (1978). Severity of prescribed penalty and mock jurors' verdicts.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(12), 1431–1442.

Kogan, Due north., & Wallach, M. A. (1967). Risky-shift miracle in small decision-making groups: A test of the information-commutation hypothesis.Periodical of Experimental Social Psychology, three, 75–84.

Kramer, R. 1000. (1998). Revisiting the Bay of Pigs and Vietnam decisions 25 years later: How well has the groupthink hypothesis stood the test of fourth dimension?Organizational Behavior and Homo Decision Processes, 73(2–3), 236–271.

Kroon, Thousand. B., Van Kreveld, D., & Rabbie, J. Thou. (1992). Group versus individual decision making: Furnishings of accountability and gender on groupthink.Small Grouping Research, 23(4), 427-458.

Larson, J. R. J., Foster-Fishman, P. Grand., & Keys, C. B. (1994). The word of shared and unshared data in decision-making groups.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 446–461.

Lieberman, J. D. (2011). The utility of scientific jury pick: Still murky later on 30 years.Electric current Directions in Psychological Scientific discipline, 20(1), 48–52.

MacCoun, R. J., & Kerr, N. Fifty. (1988). Asymmetric influence in mock jury deliberation: Jurors' bias for leniency.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 21–33.

Mackie, D. M. (1986). Social identification furnishings in group polarization.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, l(4), 720–728.

Mackie, D. M., & Cooper, J. (1984). Attitude polarization: Effects of group membership.Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, u575–585.

Matusitz, J., & Breen, 1000. (2012). An examination of pack journalism as a form of groupthink: A theoretical and qualitative analysis.Journal Of Human Behavior In The Social Environs, 22 (7), 896-915.

McCauley, C. R. (1989). Terrorist individuals and terrorist groups: The normal psychology of extreme beliefs. In J. Groebel & J. H. Goldstein (Eds.),Terrorism: Psychological perspectives (p. 45). Sevilla, Spain: Universidad de Sevilla.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., DeChurch, 50. A., Jimenez-Rodriguez, M., Wildman, J., & Shuffler, M. (2011). A meta-analytic investigation of virtuality and information sharing in teams.Organizational Behavior and Human Conclusion Processes, 115(2), 214–225.

Mojzisch, A., & Schulz-Hardt, Southward. (2010). Knowing others' preferences degrades the quality of grouping decisions.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(v), 794–808.

Morrow, K. A., & Deidan, C. T. (1992). Bias in the counseling process: How to recognize and avoid information technology. Periodical of Counseling and Development, 70, 571-577.

Myers, D. M. (1982). Polarizing furnishings of social interaction. In H. Brandstatter, J. H. Davis, & G. Stocher-Kreichgauer (Eds.),Contemporary bug in group decision-making (pp. 125–161). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Myers, D. Grand., & Bishop, G. D. (1970). Discussion furnishings on racial attitudes.Science, 169(3947), 778–779. doi: 10.1126/scientific discipline.169.3947.778

Myers, D. G., & Kaplan, M. F. (1976). Group-induced polarization in simulated juries.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2(one), 63–66.

Najdowski, C. J. (2010). Jurors and social loafing: Factors that reduce participation during jury deliberations.American Periodical of Forensic Psychology, 28(two), 39–64.

Osborn, A. F. (1953).Applied imagination. Oxford, England: Scribner's.

Paulus, P. B., & Dzindolet, M. T. (1993). Social influence processes in group brainstorming.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(iv), 575–586.

Redding, R. E. (2012). Likes concenter: The sociopolitical groupthink of (social) psychologists.Perspectives On Psychological Science, 7 (5), 512-515.

Reimer, T., Reimer, A., & Czienskowski, U. (2010). Decision-making groups attenuate the discussion bias in favor of shared information: A meta-analysis.Advice Monographs, 77(1), 121–142.

Reimer, T., Reimer, A., & Hinsz, 5. B. (2010). Naïve groups can solve the hidden-profile problem.Human Communication Research, 36(3), 443–467.

Siau, K. L. (1995). Group inventiveness and technology.Psychosomatics, 31, 301–312.

Stasser, M., Kerr, N. L., & Bray, R. M. (1982). The social psychology of jury deliberations: Structure, process and product. In Northward. L. Kerr & R. Thousand. Bray (Eds.),The psychology of the courtroom(pp. 221–256). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Stasser, G., & Stewart, D. (1992). Discovery of hidden profiles by decision-making groups: Solving a trouble versus making a judgment.Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 63, 426–434.

Stasser, One thousand., & Taylor, L. A. (1991). Speaking turns in face-to-face discussions.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60,675–684.

Stasser, G., Taylor, L. A., & Hanna, C. (1989). Information sampling in structured and unstructured discussions of 3- and half-dozen-person groups.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(1), 67–78.

Stasser, Grand., & Titus, W. (1985). Pooling of unshared data in grouping conclusion making: Biased information sampling during discussion.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(6), 1467–1478.

Stein, G. I. (1978). Methods to stimulate creative thinking.Psychiatric Annals, eight(iii), 65–75.

Stoner, J. A. (1968). Risky and cautious shifts in grouping decisions: The influence of widely held values.Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4, 442–459.

Stroebe, Westward., & Diehl, Chiliad. (1994). Why groups are less effective than their members: On productivity losses in thought-generating groups.European Review of Social Psychology, v, 271–303.

Valacich, J. S., Jessup, Fifty. Chiliad., Dennis, A. R., & Nunamaker, J. F. (1992). A conceptual framework of anonymity in group support systems.Group Decision and Negotiation, i(iii), 219–241.

Van Swol, L. M. (2009). Extreme members and group polarization.Social Influence, 4(3), 185–199.

Vinokur, A., & Burnstein, Due east. (1978). Novel argumentation and mental attitude change: The example of polarization post-obit grouping word.European Journal of Social Psychology, 8(iii), 335–348.

Watson, Yard. (1931). Do groups remember more effectively than individuals? In G. Potato & L. Murphy (Eds.), Experimental social psychology. New York: Harper.

Winter, R. J., & Robicheaux, T. (2011). Questions almost the jury: What trial consultants should know about jury determination making. In R. L. Wiener & B. H. Bornstein (Eds.),Handbook of trial consulting (pp. 63–91). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Wittenbaum, G. Thousand. (1998). Information sampling in decision-making groups: The impact of members' task-relevant status.Small Group Research, 29(ane), 57–84.

Zhu, H. (2010).Group polarization on corporate boards: Theory and show on board decisions about acquisition premiums, executive bounty, and diversification. (Doctoral dissertation). University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Ziller, R. (1957). Grouping size: A determinant of the quality and stability of group decision. Sociometry, xx, 165-173.

doughertyquart1992.blogspot.com

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/socialpsychology/chapter/group-decision-making/